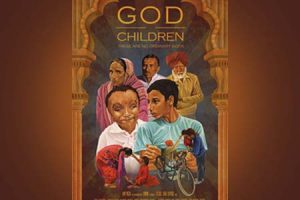

Dubai-based lecturer and filmmaker, Reshel Shah Kapoor and DoP Arith Sudhakaran speak to BroadcastPro ME about filming "God Children" in India.

In a crowded marketplace, 17-year-old Arshad mocks his friend Jaspal and says: You tried to get that girl, but when she saw you, she ran away. The audience at the private screening of Reshel Shah Kapoor’s third documentary film God Children, at OSNs Asli studio, laughs at the teenage boys ribbing each other. The conversation could have taken place in Dubai, New York or, as in this case, the rural hinterlands of northern India.

In a crowded marketplace, 17-year-old Arshad mocks his friend Jaspal and says: You tried to get that girl, but when she saw you, she ran away. The audience at the private screening of Reshel Shah Kapoor’s third documentary film God Children, at OSNs Asli studio, laughs at the teenage boys ribbing each other. The conversation could have taken place in Dubai, New York or, as in this case, the rural hinterlands of northern India.

In a particularly telling scene, the same Arshad, who cannot walk, sits in his dark room and refuses to say anything about his estranged father. I dont want to speak anymore, he says and turns his face away, his expressive eyes filling with tears. You squirm uncomfortably as the camera lingers on his distraught face.

In the space of 72 minutes, the filmmaker takes the international audience through a roller coaster of emotion. Protagonists Arshad and Pranshu are born with birth defects and deified as Hindu deities. Their world is familiar, almost clichéd, yet incredibly strange at the same time. With a straightforward storytelling technique, Reshel lets you enter their precarious worlds, mired in superstition, handicap and grinding poverty. She lets you fall in love with the boys, lets you feel anger with a society that enables exploitation, and leaves you with a pang for what could have been.

Our promo video got 2.8 million views While film festivals are a great platform, this movie needs to be watched by everyone Reshel Shah Kapoor, Director and Producer

The documentary is set for release later this year, and Reshel believes the audience needs to be more than just the film festival circuit. She is targeting digital platforms so it can reach a wider audience.

We had a promo video after the trailer in April 2018 that got 2.8 million views. The conversations it started were incredible, with people from different backgrounds weighing in. While film festivals are a great platform, this movie needs to be watched by everyone, she asserts.

We speak to Reshel and her DoP Arith Sudhakaran just as she is putting together her marketing strategy for the film. She recalls the gruelling 40-day shoot in the slums of Mumbai, for her first feature-length documentary on the citys transgender people. She had promised herself an easier movie the next time around. Maybe filming flowers or something, she had joked then.

Travelling to villages in northern India at the height of winter is a far cry from easy. Especially when she had just the names and a couple of grainy YouTube videos to go by. No addresses.

Armed with this paltry knowledge, her Mumbai-based Associate Producer Mohammed Hamati found the boys in three weeks and set the ball rolling in July 2017. What followed was a first meeting, a trailer and an extensive process of pitching for finances.

Reshel recalls: We filmed the trailer in four days on our first visit. The editing was done in a week and sound design and music in 48 hours. With this trailer and a 28-page treatment, I approached potential financiers.

Support came from Dubai-based businessman Kish Pagarani. Equipment was offered by Sony Middle East.

Reshel admits that the finances made all the difference I had an executive producer who provided the funds, and it was not a small amount. It allowed us to make a good film. While every person on the crew is understandably passionate about filmmaking, all of them got remunerated for their efforts.

The finances allowed her to invest in superior lapel mics. Poor audio can play a role in hampering documentaries from getting good distributors. On her decision to buy two DPA mics, she says, No one should come back and say the audio wasnt right. The mics were so good that it picked up audio from people not wearing the lapel mics as well. With five channels of sound, we had our bases covered. I also had Dubai-based music composer Reiner Earlings, who did both the music composition and the sound mixing and mastering in post, helping me streamline the production process.

For any documentary, it is crucial to have a skeletal crew. Also, we cant have too much gear. You dont want to spend three hours setting up Arith Sudhakaran, DoP

Having worked on production sets since her school days in the UK, Reshel, who is now a full-time senior lecturer on documentary filmmaking at Dubais SAE, ensured an efficient 17-day shoot and an editing process that spanned an incredible 23 days.

One of the big secrets to the workflow efficiency was having a full-fledged production team on board. I had a production team of four people, she reveals. I had a location manager-cum-production manager. I had an associate producer, a directors assistant and a producers assistant. This made a big difference. They combined to be the producer on set, and I was pure director. We were in sync and completely prepped before the first day of the shoot.

The extensive prepping was critical. When the crew landed in Delhi and drove the 40km to Arshads house, the 17-year-old teenager and his grandparents met Reshel and her team like old friends.

Creating a bond with the families was intrinsic to the process of filming, DoP Arith Sudhakaran explains.

We had gone on a recce a few months prior to filming. The idea was to see the location and meet the people, especially the protagonists. It is important to establish a relationship with the subjects, so they open up to you. Holding a camera in peoples faces can be intimidating.

In the film, 12-year-old Pranshu speaks of his life being regarded as Ganesh, the Hindu deity of education and all things auspicious. Arshad is visibly agitated when he is informed that he needs to bless someone as Hanuman, the monkey deity in the Hindu pantheon. The connection Reshels team created with the two families cannot be overstated, especially when the big question that made her venture into this project was: Are these children happy being deified?

The all-important interview was left for last.

Shah explains: I wanted to really observe the boys for the first few days. Arshad was giving more and more of himself telling us more stories so by the last day we had created enough trust with him to ask him about his father, and while he is still not comfortable talking about his father, he was okay with us being with him in that small room as he struggled with the question.

Despite the preparation and multiple visits, there were surprises, as every documentary filmmaker must expect. Arshads cynical, grown-up attitude was a surprising turnaround for the team, who had encountered a much more childish boy on their first two meetings. The far bigger surprise was Pranshus mother, whose views on her son being deified, were both startling and totally unexpected.

When it came to the audience, Shah chose animation to explain the religion and its mythology: Since I did not want to get into issues of copyright, I had the animation created by artists Kristy Ligones and Pauleen Vecino. I needed an international audience to know what Hanuman and Ganesh looked like and that there were other deities, and why devotees prayed to them.

On decisions around the size of the crew, the gear and the almost 9-to-5 nature of the shoot, Sudhakaran explains: For any documentary, it is crucial to have a skeletal crew. Also, we cant have too much gear. With fiction, you can light as much as you want, add and remove elements but here you are in someones house. You work with what you have, and you operate quickly. You dont want to spend three hours setting up. Having a 15-hour day in someones house does not help.

Going for the trailer helped me know where I would shoot and what gear and lights I would need. One or two set-ups, such as the interaction between the grandfather and grandmother, were elaborate. We had seven or eight sources of light for that scene.

On choosing a relatively small camera, Sudhakaran says: We had support from Sony. I insisted that the camera had to be small. We were shooting in villages and it had to be less intimidating. Also, large cameras can create a mistaken belief that we have a lot of money. We chose to use the Sony A7s2 because it has great features. You can shoot in really dark corners. It is incredibly versatile and lightweight. We had one tripod and two monopods and one gimbal, and the camera works with all of these accessories.

For the deceptively simple shot of Arshad and Jaspal walking into the crowded market, Sudhakaran chose long lenses. It was an elaborate set-up. We were using long lenses for closeup shots. Its tricky holding focus using long lenses. The effect is incredible though, as it isolates the subject from the crowd.

With six days for each boy, a couple of days for B-roll and interviews and a couple of days off, the 17-day shoot was intense but built around extensive research and a clear understanding of what was needed for the story.

The editing was another breathtakingly efficient process that lasted 23 days.

Shah elaborates: We had 13 hours of interviews. Our last interview with Arshad is possibly 13 minutes long on screen. It was, however, a four-hour-long interview in raw footage. We had a Hindi translator insert all the subtitles before any of us saw the footage. Four of us, including myself, the editor, the assistant editor and my production assistant, then watched all the footage and made notes. We picked what we wanted and created the story on slips of paper, based on the issues we wanted covered around every person. Everything was colour coordinated, so for instance the green slips related to B-roll for the grandfather. This process took a week or so. Working with Robbie Perena, my editor, I then followed through on our initial selection, moving scenes around and timing the sequences as we went along.

The 23-day, 9am-6pm editing schedule with weekends off, including one day at the cinema, was critical because every member of the crew also had a day job to get back to.

Reflecting on the relatively smooth process of production, Shah says: As a director, my main job was with the people on camera. My camera and sound departments, along with my producers, needed to know as much about the vision for the film as I did. This is my third film with Arith and we were in perfect sync.

More than one crew member, including music composer Reiner Erlings (see box), speaks of Reshel’s collaborative approach to filmmaking. The film teacher in Reshel would possibly discuss elements of cinema verité, expository and observational documentary filmmaking her film has elements of all these approaches, along with a zeal to highlight social injustices.

This zeal has underlined all of Reshels filmmaking. A recent short film was about the UAEs undertaker, Ashraf Thamarassery, who helps repatriate bodies of poor immigrants to their home countries. In Black Sheep, you see a group of Mumbais transgender women relate to the audience as the women they want to be.

There is an ease to Reshel’s storytelling, and only a conversation with her reveals the many decisions that go into lighting or shooting every scene.

In the final moments of the film, Arshad breaks into a haunting song and the camera pans to the grandmother, sitting and listening in the setting sun.

It was a moment of movie magic that just happened, recalls Reshel. This is the grandmother regretting the choices she made for Arshad, and you wonder if Pranshus mother will have similar regrets in ten years time.

Arshads song fades as the credits roll, and the room erupts in applause. The images of the two extraordinary and wonderfully articulate boys will linger. You will also marvel at a difficult story told well.

At the time of going to press, Reshel Shah Kapoor informed us that the documentary has been picked up by London-based distribution company, Journeyman Pictures.

Reiner Erlings, the Dubai-based music composer and sound mixer for the film, speaks about the process.

On composing the music:

On composing the music:

I was lucky enough to be involved with this project right from the very beginning, when it was still in the development phase. Reshels brief was to create a score that supports the narrative and ties the two distinct storylines together. I started by composing the main theme music, as well as a theme for each of the two main characters, Arshad and Pranshu. As the edit developed and I saw more of the footage, I was able to delve a little deeper and compose sub-themes for some of the main supporting characters, such as Arshads grandparents and Pranshus father.

By the time the edit was locked, most of the main musical ideas were already approved and I was then able to finalise the score and also record the live instrumentation. I worked with an amazing cellist and bansuri flute player for this score, whom I feel added a tremendous amount of human emotion and authenticity to the music.

On the equipment and software used:

Hardware-wise, I have a simple set-up at my studio, with a UA apollo converter, Neve 500 series pre-amps and Genelec monitoring system (8050s with the 7070 sub, as well as a pair of the classic 3010s). My main DAW is Logic X, which I have been using since 2004. I use plug-ins from Universal Audio, Waves, and for this project I mainly used sample libraries for EastWest, Native Instruments, Omnisphere and Spitfire.

On the challenges:

My main challenge was to compose the music in such a way that it did the story justice and also remained authentic and respectful of the films setting. Fortunately, Reshel trusted me with this responsibility and it is a testament to how she is as a filmmaker she empowers those in her team and doesn’t micromanage.

On the sound mixing process:

The film is set in rural Punjab, in small villages. The brief was to recreate the sonic landscape of this area in a way that is authentic. I used Logic X for the final audio mix.

On sound design and Foley work:

I did a lot of Foley and sound design for this film. Besides creating an authentic Punjabi village atmosphere, from quiet mornings to bustling market scenes, I also had to recreate almost every action sound you hear in the film. This included everything from birds chirping, ladies sweeping, motorcycles driving by, cooking on open fires, footsteps, etc. In some cases, such as a street vendor preparing a local snack known as pani puri, this ended up becoming quite an elaborate project. Overall, I would say that the Foley and sound design took almost as long as it did to compose all the music, but in the end I think it really contributed to making the film sound real and authentic.